Overview

We focused on a small sample of videos captured in Sunset Park, Brooklyn between 2002-2014 — a largely Latinx and Asian community. A significant portion of the collection was from the annual Puerto Rican Day Parade — an event that has been met with recurring police abuse. The videos in the collection were filmed by or directly shared with El Grito de Sunset Park.

These videos, related media and court documents showed certain officers that have been repeatedly involved in violent altercations with the community year after year. And, despite this history of abuse, negative media, and videos showing violent acts — these abusive officers often continue to serve on the NYPD and receive promotions and overtime.

ABOUT THE VIDEOS

Sample Size Details

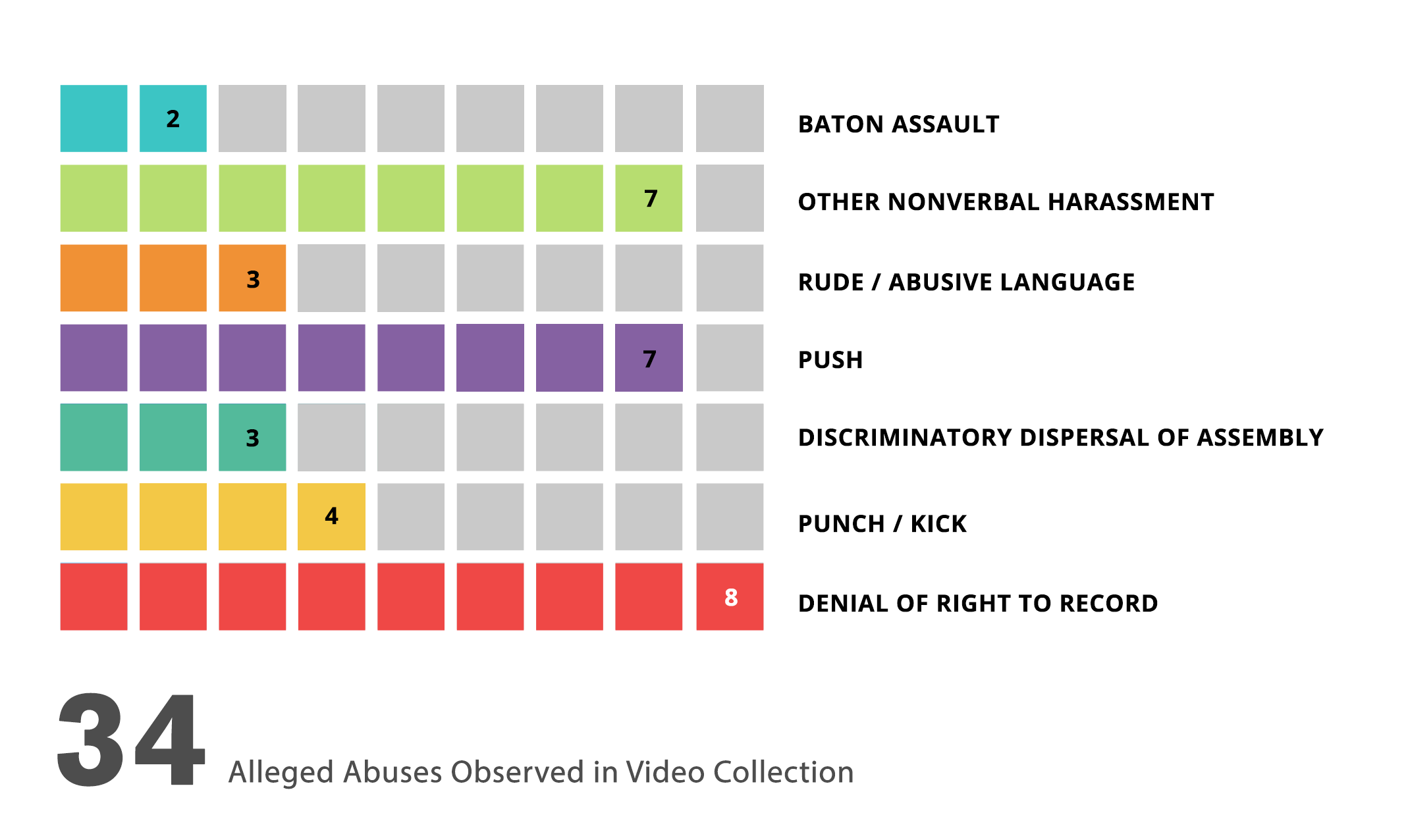

Alleged Abuses Observed in Video Collection

This chart represents a sample selection of the types of alleged abuses documented in the video collection. Many videos showed likely abuses, such as use of excessive force and use of offensive language. We tagged these videos using terms from from in the NYPD Patrol Guide and other copwatch patrol forms. This is not a comprehensive representation of the types of misconduct observed in the videos, but offers a snapshot of the limited selection we reviewed.

Some of the incidents in the database were documented by multiple people, showing different angles and perspectives as events unfolded. For the creation of this graphic, abuses and alleged abuses shown in the videos were only counted one time, even when the same abuse was shown in multiple videos.

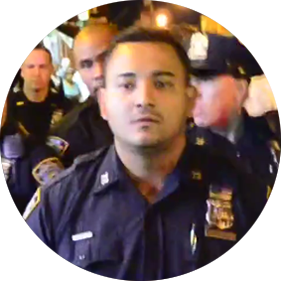

Officer Profile

The El Grito Police Profile represents one example of how to examine multiple videos of police abuse in relation to other information sources. The officer reviewed here — Ciardiello — featured multiple times in the videos we reviewed and in the stories we heard from activists. He is known in the community, by legal services providers, is named in numerous court cases, has been subject of negative media reports, and yet receives regular raises and promotions. Learn more and see full profile here.

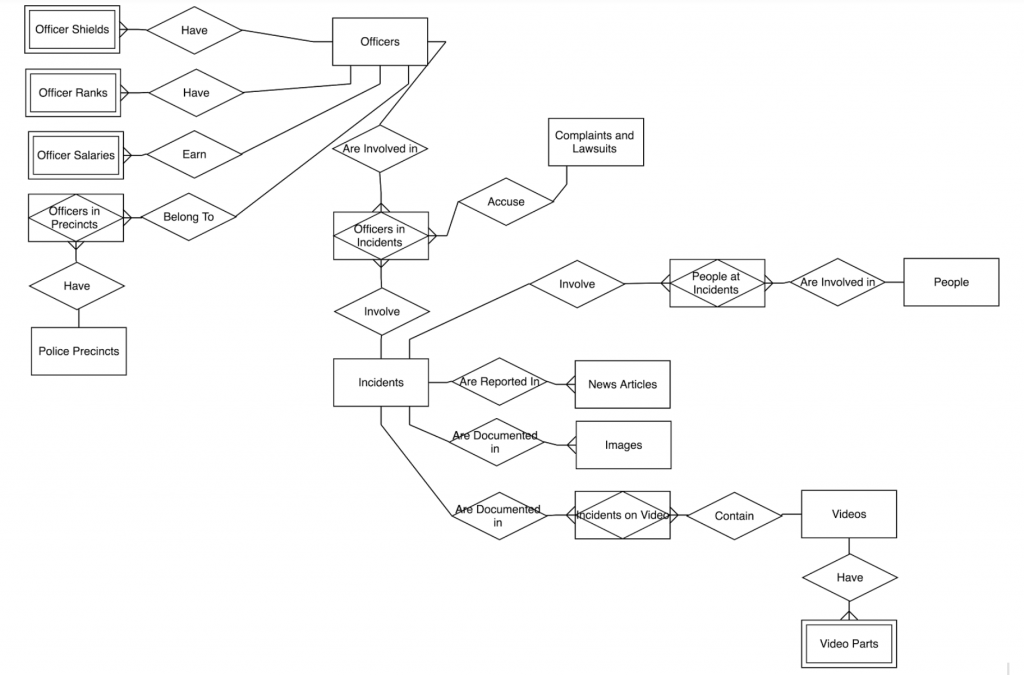

Working With Metadata

Simply put, metadata is data about data. Metadata is essential because it makes it possible to identify, find, understand and analyze video. For example, knowing where a video was shot, when, and by whom, is extremely important for understanding the video content.

As a first step towards creating a database structure for El Grito’s videos, we collected and created metadata for the videos in this project. We took an organic approach to this process, starting with a very limited set of assumptions and working in close collaboration with El Grito to review, verify and tag the videos. Based on our process and learnings from tagging and describing the videos, we explored ways to best structure the data and came up with a sample metadata model.

Tagging and describing the videos with no pre-defined metadata structure in place was valuable in many ways, but a lot of labor for our team. So at the end of the tagging process, we used our our learnings and outputs to develop a reusable data model that others could take advantage of, use, or adapt, instead of having to start from scratch. Ultimately, if we and others can refine this into a community standard we can all use, it will enable us to exchange information more easily between organizations, and to identify patterns of police abuse across communities.